Archaeology at Curles Neck 44HE388

This summary is based on :

- Five "Mansion Houses" of Curles Plantation, ca. 1630-1860

Paper (PDF) presented at the Society for Historical Archaeology Conference, 1997. L. Daniel Mouer, Ph.D. Virginia Commonwealth University

The Harris Mansion (1630 to 1660)

The Curles Neck tract may have been settled by English colonists as early as the 1610s. Daniel Mouer has argued that Digges’s Hundred, part of the “New Bermudas” community settled by Sir Thomas Dale in 1614, was located on Curles Neck. The lieutenant of Digges’s Hundred at the time of the 1622 Algonquian uprising was Thomas Harris, a military man who had come to Virginia with Dale. By the 1630s, Harris had purchased a substantial plantation on Curles Neck (which he may have called Longfield), which corresponds to the construction of the first large mansion house at 44HE388. Harris’ seat was a “cellar house” with the first floor (or low room) sunk most of the way into the ground and only the second floor (if it existed) fully extending above the ground level. Dan Mouer has argued that the second floor may have jutted out beyond the wall line of the first floor, creating a foot or two of overhang. While the structure was supported with large wooden posts sunk directly into the ground like most other 17th-century English structures in the Chesapeake, the spaces between these posts were filled (or nogged) with bricks at least as high as the ceiling of the low room. The Harris mansion had a roughly 7.5 x 8 ft., centrally placed “I” hearth with a brick chimney built on a cut granite foundation which divided the low room into east and west wings. The east wing appears to have been built in the 1630s with the west wing likely added at a later point in time. The majority of the archaeological remains of the west wing were destroyed in 1676 during the construction of defensive works during Bacon’s Rebellion, making it difficult to accurately date the sequence of construction and repair episodes of Harris’ mansion. The east wing of the structure was roughly 28 ft. long and 19 ft. wide, with structural posts spaced about 7 ft. apart. The floor of the east wing, and the surviving portion of the west wing, was paved with brick. A beehive baking oven was inserted into the southern wall of the structure directly south of the central hearth. The firebox and oven door faced into the low room, but the main structure of the oven stood outside of the house. Archaeological evidence suggests that the Harris mansion burned down and was abandoned sometime in the 1660s. Layers of charred remains were capped by rubble as the brick walls fell into the low room. The rest of the room was filled with rubble and then covered with a thick layer of soil to create an artificial terrace.

The Curles Neck tract may have been settled by English colonists as early as the 1610s. Daniel Mouer has argued that Digges’s Hundred, part of the “New Bermudas” community settled by Sir Thomas Dale in 1614, was located on Curles Neck. The lieutenant of Digges’s Hundred at the time of the 1622 Algonquian uprising was Thomas Harris, a military man who had come to Virginia with Dale. By the 1630s, Harris had purchased a substantial plantation on Curles Neck (which he may have called Longfield), which corresponds to the construction of the first large mansion house at 44HE388. Harris’ seat was a “cellar house” with the first floor (or low room) sunk most of the way into the ground and only the second floor (if it existed) fully extending above the ground level. Dan Mouer has argued that the second floor may have jutted out beyond the wall line of the first floor, creating a foot or two of overhang. While the structure was supported with large wooden posts sunk directly into the ground like most other 17th-century English structures in the Chesapeake, the spaces between these posts were filled (or nogged) with bricks at least as high as the ceiling of the low room. The Harris mansion had a roughly 7.5 x 8 ft., centrally placed “I” hearth with a brick chimney built on a cut granite foundation which divided the low room into east and west wings. The east wing appears to have been built in the 1630s with the west wing likely added at a later point in time. The majority of the archaeological remains of the west wing were destroyed in 1676 during the construction of defensive works during Bacon’s Rebellion, making it difficult to accurately date the sequence of construction and repair episodes of Harris’ mansion. The east wing of the structure was roughly 28 ft. long and 19 ft. wide, with structural posts spaced about 7 ft. apart. The floor of the east wing, and the surviving portion of the west wing, was paved with brick. A beehive baking oven was inserted into the southern wall of the structure directly south of the central hearth. The firebox and oven door faced into the low room, but the main structure of the oven stood outside of the house. Archaeological evidence suggests that the Harris mansion burned down and was abandoned sometime in the 1660s. Layers of charred remains were capped by rubble as the brick walls fell into the low room. The rest of the room was filled with rubble and then covered with a thick layer of soil to create an artificial terrace.

The Bacon Mansion (1670 to 1700)

.jpg) In the mid-1670s Nathanial Bacon constructed a “small new brick house” on his newly-purchased property on Curles Neck. The archeological remains of this structure consist of a 20 x 20 ft. brick cellar with a tile floor found a few feet south of the Harris mansion. Dan Mouer has argued that this structure was completely constructed of brick, in the baroque style associated with Christopher Wren. Bacon’s cellar had a small brick hearth built into its eastern wall that would have extended into the upper rooms of the house. From 1655 to 1675, prior to Bacon’s occupancy, the Curles Neck property was owned by Thomas Ballard, an absentee landowner who rented the land to tenants. There is some archaeological evidence that after the Harris mansion burned down he constructed an earthfast structure in the area directly west of Bacon’s brick house, which may have been incorporated into the brick structure and called the “old hall” in a 1677 inventory of the property. Several large postholes have been found in this area, but more research is needed to determine their construction dates and associations. By far the most extensive modifications made during the three years Bacon owned the property were the extensive fortifications constructed around the plantation core.

In the mid-1670s Nathanial Bacon constructed a “small new brick house” on his newly-purchased property on Curles Neck. The archeological remains of this structure consist of a 20 x 20 ft. brick cellar with a tile floor found a few feet south of the Harris mansion. Dan Mouer has argued that this structure was completely constructed of brick, in the baroque style associated with Christopher Wren. Bacon’s cellar had a small brick hearth built into its eastern wall that would have extended into the upper rooms of the house. From 1655 to 1675, prior to Bacon’s occupancy, the Curles Neck property was owned by Thomas Ballard, an absentee landowner who rented the land to tenants. There is some archaeological evidence that after the Harris mansion burned down he constructed an earthfast structure in the area directly west of Bacon’s brick house, which may have been incorporated into the brick structure and called the “old hall” in a 1677 inventory of the property. Several large postholes have been found in this area, but more research is needed to determine their construction dates and associations. By far the most extensive modifications made during the three years Bacon owned the property were the extensive fortifications constructed around the plantation core.

.jpg) These included a tunnel, or mine, that extended west from the brick cellar, a ditch encircling the perimeter of the fortifications and an armory or storehouse built where the western wing of the Harris Mansion once stood. Excavations into the tunnel found the charred remains of wooden beams, which may have been used to support the earthen roof. Bacon’s mansion seems to have burned down sometime after his death in 1677, but the remnants of his fortifications were apparently still visible on the landscape in the early 19th century. No definitive palisade lines were identified during excavation; thus, the only evidence of the size and shape of the fortifications is provided by a boundary ditch. Only a small section of the ditch running north-south to the west of Bacon’s mansion has been uncovered thus far, but Dan Mouer has suggested that it may have encompassed over an acre of land.

These included a tunnel, or mine, that extended west from the brick cellar, a ditch encircling the perimeter of the fortifications and an armory or storehouse built where the western wing of the Harris Mansion once stood. Excavations into the tunnel found the charred remains of wooden beams, which may have been used to support the earthen roof. Bacon’s mansion seems to have burned down sometime after his death in 1677, but the remnants of his fortifications were apparently still visible on the landscape in the early 19th century. No definitive palisade lines were identified during excavation; thus, the only evidence of the size and shape of the fortifications is provided by a boundary ditch. Only a small section of the ditch running north-south to the west of Bacon’s mansion has been uncovered thus far, but Dan Mouer has suggested that it may have encompassed over an acre of land.

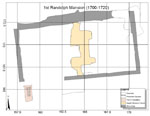

First Randolph Mansion (1700 to 1720)

In 1699, William Randolph, the owner of the Turkey Island plantation located near 44HE388, purchased the Curles Neck plantation. Sometime between 1700 and his death in 1711, Randolph began construction of a new mansion on the property, likely intended for his son William II. In 1715, William II gave the property to his brother Thomas Randolph. Except for a brief period from 1799 to 1809 when it was owned and occupied by William Heth, the property continued to be passed between members of the Randolph family until 1820, when it was sold to William Allen. The first Randolph mansion was built on top of the deeply buried ruins of the Harris mansion. It consisted of a 40 x 20 ft. brick structure built upon deeply set brick foundations with a spread footer. The walls were laid in Flemish bond with glazed headers, creating a checkerboard pattern. Rubbed soft bricks surrounded windows and possibly the doorways. A water table course of beveled bricks belted the building. The entry doors stood near the western end of the house and part of the brick porch foundation was found archaeologically. The structure was likely only one story high with a loft or garret under the roof. The house would have had a central brick “I” hearth, but the original chimney was extensively modified when the structure was renovated into a detached kitchen. The floors of the first Randolph mansion were wooden planks resting on joists. Few features outside the structure associated with its use as a plantation seat have been definitively identified, but the location of the porch and entryway facing south suggests that outbuildings or work spaces associated with Bacon’s mansion may still have been in use during the first few decades of Randolph occupancy.

In 1699, William Randolph, the owner of the Turkey Island plantation located near 44HE388, purchased the Curles Neck plantation. Sometime between 1700 and his death in 1711, Randolph began construction of a new mansion on the property, likely intended for his son William II. In 1715, William II gave the property to his brother Thomas Randolph. Except for a brief period from 1799 to 1809 when it was owned and occupied by William Heth, the property continued to be passed between members of the Randolph family until 1820, when it was sold to William Allen. The first Randolph mansion was built on top of the deeply buried ruins of the Harris mansion. It consisted of a 40 x 20 ft. brick structure built upon deeply set brick foundations with a spread footer. The walls were laid in Flemish bond with glazed headers, creating a checkerboard pattern. Rubbed soft bricks surrounded windows and possibly the doorways. A water table course of beveled bricks belted the building. The entry doors stood near the western end of the house and part of the brick porch foundation was found archaeologically. The structure was likely only one story high with a loft or garret under the roof. The house would have had a central brick “I” hearth, but the original chimney was extensively modified when the structure was renovated into a detached kitchen. The floors of the first Randolph mansion were wooden planks resting on joists. Few features outside the structure associated with its use as a plantation seat have been definitively identified, but the location of the porch and entryway facing south suggests that outbuildings or work spaces associated with Bacon’s mansion may still have been in use during the first few decades of Randolph occupancy.

Second Randolph Mansion (1720 to 1775)

.jpg) Sometime in the 1720s, construction began on a large frame mansion about 50 ft. northwest of the first Randolph mansion. The earliest phase of this structure consisted of a 40 x 26 ft. structure built over a full basement with brick walls. Unlike the first Randolph mansion, the brick foundations of this structure were much less substantial, suggesting that the building was frame rather than brick, and two stories tall rather than one. In the 1740s this structure was significantly expanded. A central passage and a 35 x 26 ft. wing was added to the western side of the original structure. Massive chimneys stood at both ends of the now 85-foot-long house, attached to end-walls which were built entirely of brick. There were no internal chimneys. During the winter months, the center passage and the rooms on either side of the passage were unheated. Entryways were placed at both the northern and southern ends of the passage. A brick porch was placed at the southern entrance, while a stone stoop decorated the northern one. The mansion likely had a wooden roof and a wooden floor.

Sometime in the 1720s, construction began on a large frame mansion about 50 ft. northwest of the first Randolph mansion. The earliest phase of this structure consisted of a 40 x 26 ft. structure built over a full basement with brick walls. Unlike the first Randolph mansion, the brick foundations of this structure were much less substantial, suggesting that the building was frame rather than brick, and two stories tall rather than one. In the 1740s this structure was significantly expanded. A central passage and a 35 x 26 ft. wing was added to the western side of the original structure. Massive chimneys stood at both ends of the now 85-foot-long house, attached to end-walls which were built entirely of brick. There were no internal chimneys. During the winter months, the center passage and the rooms on either side of the passage were unheated. Entryways were placed at both the northern and southern ends of the passage. A brick porch was placed at the southern entrance, while a stone stoop decorated the northern one. The mansion likely had a wooden roof and a wooden floor.

.jpg) During this same period the first Randolph mansion was renovated into a detached kitchen. As part of this process, the central hearth was expanded, especially the side accessed from the western room, a baking oven was added, and a brick wall was constructed that completely separated the two original rooms. At the same time a 10 x 20 ft. room was added to the west of the structure. This new room was likely used for food storage and had a gravel floor. These renovations coincided with the removal of the porch on the southern wall and the addition of a brick porch in the center of the eastern wall of the structure. It is also likely that at this time an entryway was added in the northern wall of the kitchen structure. There are several archaeological features created during this period relating to the use of this building as a kitchen. A sub-floor pit was placed in front of the hearth in the easternmost room, a rain-barrel cistern stood on a gravel pad at the southeastern corner of the kitchen, and a brick well was dug into the edge of the terrace to the south of the kitchen. Overflow from the cistern was channeled into a drain that led down the first terrace slope to a deep pit dug into the Bacon mansion cellar fill. The pit was filled with faunal remains and trash from the mid to late 18th century. Dan Mouer interpreted this feature as a "stewpond" that provided both water and fertilizer for the kitchen gardens.

During this same period the first Randolph mansion was renovated into a detached kitchen. As part of this process, the central hearth was expanded, especially the side accessed from the western room, a baking oven was added, and a brick wall was constructed that completely separated the two original rooms. At the same time a 10 x 20 ft. room was added to the west of the structure. This new room was likely used for food storage and had a gravel floor. These renovations coincided with the removal of the porch on the southern wall and the addition of a brick porch in the center of the eastern wall of the structure. It is also likely that at this time an entryway was added in the northern wall of the kitchen structure. There are several archaeological features created during this period relating to the use of this building as a kitchen. A sub-floor pit was placed in front of the hearth in the easternmost room, a rain-barrel cistern stood on a gravel pad at the southeastern corner of the kitchen, and a brick well was dug into the edge of the terrace to the south of the kitchen. Overflow from the cistern was channeled into a drain that led down the first terrace slope to a deep pit dug into the Bacon mansion cellar fill. The pit was filled with faunal remains and trash from the mid to late 18th century. Dan Mouer interpreted this feature as a "stewpond" that provided both water and fertilizer for the kitchen gardens.

Third Randolph Mansion (1775 to 1860)

.jpg) Sometime in the third quarter of the 18th century, the house and grounds at Curles Neck went through a major renovation. While the floorplan of the mansion was not extensively modified during this event, the number and varieties of specialized outbuildings that were constructed at this time, in addition to the changes to the surrounding landscape, suggest that there were significant changes in the organization of the Randolph household. Spaces outside the mansion proper were formalized, creating a carefully organized complex of buildings, gardens, and pathways that extended for more than 100 m around the mansion house and presented viewers with a tableau which spoke to the economic and political power of the Randolph family. The first major modification of the mansion house itself was the extension of the eastern wing 10 ft. to the east. This extension required moving the northern and southern entryways to maintain a symmetrical fa?ade and extending the bulkhead entrance to the cellar 10 ft. further east under the new addition. As part of this process, the stone stoop in front of the northern door was replaced with a Neoclassical portico with wooden columns perched on pyramidal bases of English sandstone constructed to frame the entry. The basement of the mansion contained a warming kitchen, a food storage room (the floor of which was rammed earth laid over a thick layer of broken bottle glass as a barrier to vermin) and a wine cellar that held a barrel stand. A stairway from the cellar probably led to the central passage on the first floor. Polished stone fireplace surrounds and huge quantities of plaster recovered archaeologically give some indication of how the interior of the structure once looked.

Sometime in the third quarter of the 18th century, the house and grounds at Curles Neck went through a major renovation. While the floorplan of the mansion was not extensively modified during this event, the number and varieties of specialized outbuildings that were constructed at this time, in addition to the changes to the surrounding landscape, suggest that there were significant changes in the organization of the Randolph household. Spaces outside the mansion proper were formalized, creating a carefully organized complex of buildings, gardens, and pathways that extended for more than 100 m around the mansion house and presented viewers with a tableau which spoke to the economic and political power of the Randolph family. The first major modification of the mansion house itself was the extension of the eastern wing 10 ft. to the east. This extension required moving the northern and southern entryways to maintain a symmetrical fa?ade and extending the bulkhead entrance to the cellar 10 ft. further east under the new addition. As part of this process, the stone stoop in front of the northern door was replaced with a Neoclassical portico with wooden columns perched on pyramidal bases of English sandstone constructed to frame the entry. The basement of the mansion contained a warming kitchen, a food storage room (the floor of which was rammed earth laid over a thick layer of broken bottle glass as a barrier to vermin) and a wine cellar that held a barrel stand. A stairway from the cellar probably led to the central passage on the first floor. Polished stone fireplace surrounds and huge quantities of plaster recovered archaeologically give some indication of how the interior of the structure once looked.

.jpg) Directly north of the mansion lay an enclosed parterre, and just north of that was another enclosed garden containing the family cemetery. To the south of the house a series of three broad staircase terrace gardens extended more than 100 yards to an entrance gate from the road leading to the plantation landing, wharves, and warehouses on the James River. A series of formal structures extended in line with the long axis of the mansion. A 20 x 20 ft. icehouse with a brick foundation was constructed directly east of the mansion, and a second icehouse or dairy stood directly north of this structure. This second structure was mirrored by a 15 x 30 ft. plantation store off the northwest corner of the mansion. Further east, a brewhouse of unknown size and a 16 x 16 ft. laundry continued the line of formal, frame structures with brick foundations. A brick and sandstone colonnade connected the bulkhead entrance to the mansion cellar and the icehouse to the brick kitchen about 60 ft. to the south. A line of quarters which housed the plantation’s enslaved population extended south of the kitchen, perpendicular to the line of formal outbuildings. Only one of these structures has been exposed, with only a single wall mapped thus far.

Directly north of the mansion lay an enclosed parterre, and just north of that was another enclosed garden containing the family cemetery. To the south of the house a series of three broad staircase terrace gardens extended more than 100 yards to an entrance gate from the road leading to the plantation landing, wharves, and warehouses on the James River. A series of formal structures extended in line with the long axis of the mansion. A 20 x 20 ft. icehouse with a brick foundation was constructed directly east of the mansion, and a second icehouse or dairy stood directly north of this structure. This second structure was mirrored by a 15 x 30 ft. plantation store off the northwest corner of the mansion. Further east, a brewhouse of unknown size and a 16 x 16 ft. laundry continued the line of formal, frame structures with brick foundations. A brick and sandstone colonnade connected the bulkhead entrance to the mansion cellar and the icehouse to the brick kitchen about 60 ft. to the south. A line of quarters which housed the plantation’s enslaved population extended south of the kitchen, perpendicular to the line of formal outbuildings. Only one of these structures has been exposed, with only a single wall mapped thus far.

Curles Neck is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

Curles Neck is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

Archaeology Digital Data

Anthropology Department. Knoxville TN 37918

• Email: mfreem12@utk.edu

The University of Tennessee, Knoxville

Knoxville, Tennessee 37996

865-974-1000

The flagship campus of the University of Tennessee System and partner in the Tennessee Transfer Pathway.