Indian Camp

- Archaeology

- History

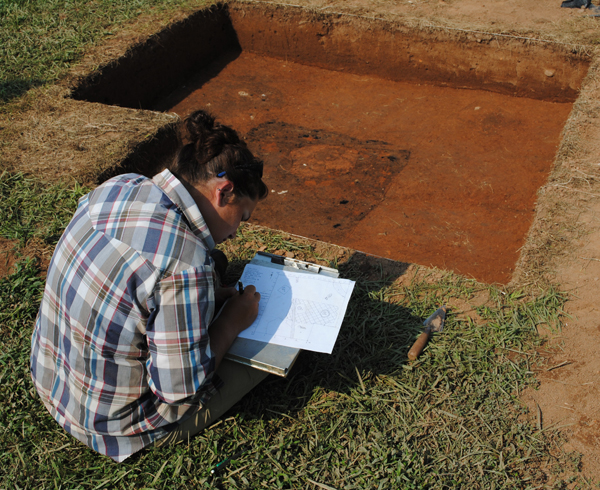

Archaeologists have searched for the houses and associated yards of the enslaved men, women, and children who lived at Indian Camp between the 1730s and the mid-1770s. In the summer of 2010 and 2011, archaeologists and field school participants from the University of Tennessee, Knoxville (UTK) conducted a shovel-test survey of portions of the historic Indian Camp property. Field work in 2010 failed to locate any historic sites associated with the Eppes-Wayles-Jefferson ownership of Indian Camp.

Archaeologists have searched for the houses and associated yards of the enslaved men, women, and children who lived at Indian Camp between the 1730s and the mid-1770s. In the summer of 2010 and 2011, archaeologists and field school participants from the University of Tennessee, Knoxville (UTK) conducted a shovel-test survey of portions of the historic Indian Camp property. Field work in 2010 failed to locate any historic sites associated with the Eppes-Wayles-Jefferson ownership of Indian Camp.

However, in 2011, archaeologists identified two sites associated with enslaved people living on the property in the late 18th-century. The first site of interest is located on a gentle slope in a wooded area above a spring. During testing, excavators found a small number of hand wrought nails and an 18th-century button or cuff link. Because the nails were relatively scarce and dispersed, we used a metal detector to locate additional "hits," and excavated a sample of them. Each contained a wrought nail or, in one case, a small, cast-iron woman's head. Further testing upslope indicated that the site might extend out of the forest to the edge of a modern field. In 2012, we conducted more extensive excavations in this area to see if we could locate features associated with a house or houses. We found a scatter of artifacts but no intact deposits relating to housing.The area has been given the site number 44PO158.

Several hundred feet to the south we located a concentration of artifacts in a plowed field that consisted of a mixture of 18th- and 19th-century ceramic wares, hand- and early machine-made nails, bottle glass, window glass, and other architectural debris. Included in the assemblage were a large number of sherds of locally-made pottery known as "colonoware." Beneath the plow zone, we uncovered the shallow remains of a small pit that had been cut through by posts for a later structure. The pit is associated with a late 18th-century, post-in-ground slave dwelling. West of the dwelling we found the remains of a boundary fence. After the dwelling was torn down, residents at the site built a small, circular or octagonal post-in-ground building that may have served as a dovecote or pigeon house for providing visitors to the nearby tavern with meat. Northeast of the slave dwelling we also found the brick foundations for a post-1820 outbuilding associated with the tavern.

In November of 1733, Francis Eppes, a prominent Virginia planter, wrote his last will and testament. In it, he bequeathed property to his three sons, his wife, and his two daughters, Ann and Martha. Together, Ann and Martha received 2400 acres of land patented by their father in 1730 in the newly formed Goochland County, just north of the Appomattox River. Ann received 1200 acres, the "lower moiety" (meaning part) along Swan's Creek. Martha received the "upper moiety" of 1200 acres between the branches of Indian Creek, including "ye house there lately built."

In November of 1733, Francis Eppes, a prominent Virginia planter, wrote his last will and testament. In it, he bequeathed property to his three sons, his wife, and his two daughters, Ann and Martha. Together, Ann and Martha received 2400 acres of land patented by their father in 1730 in the newly formed Goochland County, just north of the Appomattox River. Ann received 1200 acres, the "lower moiety" (meaning part) along Swan's Creek. Martha received the "upper moiety" of 1200 acres between the branches of Indian Creek, including "ye house there lately built."

Martha Eppes inherited Jenny, an enslaved woman, and girls Abby, Sarah, Judy, and Dinah from her father. She and Ann became co-owners of Argulus, Will and Parthena, all adults, and were instructed to divide between them any future children of Parthena. In May of 1737, Martha inherited two girls, Kate and Betty (Hemings), from her brother.

Indian Camp

The "upper moiety" given to Martha and specified in her father’s will refers to the western 1200 acres of the Eppes patent, centered on the eastern branches of Indian Camp Creek to the north and crossing south of the Buckingham Road.

Martha married Llewellin Epes in September of 1742 and was widowed within a year. What impact this first marriage had on the use of Indian Camp is not known. On May 3, 1746, she married John Wayles, an attorney and planter from Charles City County. While the couple visited their Indian Camp lands, they never lived there permanently. Martha died in 1748 following the birth of her only surviving child, also named Martha.

Martha married Llewellin Epes in September of 1742 and was widowed within a year. What impact this first marriage had on the use of Indian Camp is not known. On May 3, 1746, she married John Wayles, an attorney and planter from Charles City County. While the couple visited their Indian Camp lands, they never lived there permanently. Martha died in 1748 following the birth of her only surviving child, also named Martha.

As Martha's husband, John Wayles had rights to the Indian Camp lands for life, but he could not sell it. The transfer of property from generation to generation (usually land, but often slaves as well), without the ability to divide or sell it, was known as entail. The Indian Camp lands were entailed by Francis Eppes to pass, in perpetuity, to the descendants of his daughter.

In 1749, Goochland County was divided and Indian Camp became part of Cumberland County. During the 1750s, Wayles added to his landholdings adjacent to Indian Camp, acquiring land which he referred to as "St. James," and buying additional land along Guinea and Angola Creeks further to the west.

In 1749, Goochland County was divided and Indian Camp became part of Cumberland County. During the 1750s, Wayles added to his landholdings adjacent to Indian Camp, acquiring land which he referred to as "St. James," and buying additional land along Guinea and Angola Creeks further to the west.

Following Wayles' death in 1773, the Indian Camp lands passed to his daughter (and Francis Eppes's granddaughter), Martha Jefferson. She and her husband Thomas petitioned the General Assembly, the governing body of Virginia, for permission to "dock" (break) the entail and be allowed to sell the land. The couple sold Indian Camp, including part of the St. James property, to Henry Skipwith, Martha's brother-in-law, in 1777. The same year, Cumberland County divided, and the eastern portion, where Indian Camp was located, became Powhatan County. The land remains in Powhatan County today.

Henry Skipwith sold a portion of the property to Frances Eppes Harris (the nephew of Martha Eppes Wayles), who operated a tavern and store there in the early-19th century. In 1807, Harris sold the property to Hugh French, who continued to operate the tavern until his death in the 1840s. This portion of the property is known as “French’s Tavern” today, and was nominated to the National Register of Historic Places in 1989.

Henry Skipwith sold a portion of the property to Frances Eppes Harris (the nephew of Martha Eppes Wayles), who operated a tavern and store there in the early-19th century. In 1807, Harris sold the property to Hugh French, who continued to operate the tavern until his death in the 1840s. This portion of the property is known as “French’s Tavern” today, and was nominated to the National Register of Historic Places in 1989.